Dutchmen in Travancore

Ulloor S. Parameswara lyer

Ulloor S. Parameswara lyer

Stop way farer

Here lies Eustachius Benedictus De Lannoy, who as the General-in-chief of the troops of Travancore was in command, and for nearly 37 years served the king with the utmost fidelity.

By the might of his arms and the fear (of the name), he subjected to his (the king's)way all the kingdoms from Kayamkulam to Cochin.

He lived 62 years and 5 months and died on the 1st June 1777.

May he rest in peace.

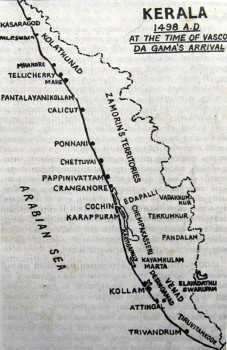

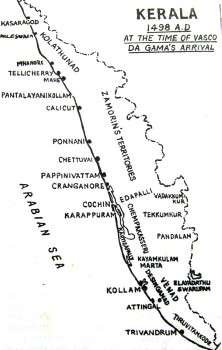

In the seventeenth century of the Christian era, five European nations, the Portuguese, the Dutch, the Danes, the English and the French traded with India on a considerable scale. Though all these possessed settlements on the Malabar Coast, only three, the Portuguese, the Dutch and the English ever seem to have striven to obtain the monopoly of the trade of Malabar. The French did not build even a single factory in Travancore, while the Dutch who actually owned two warehouses, the one at Edava in Chirayinkil and the other at Kulachel in Eraniel, were too poor and lazy to survive in the general struggle for existence. Of Edava, Captain Hamilton writes in 1700 A.D: "Thus Danes have a small factory here standing on the seaside. It is a thatched house of a very mean aspect and their trade answers every way to the figure their factory makes. "The poor Danes have also a residence in Malabar" notes J. C. Visscher in 1723 "called Eddava, resembling a miserable hut rather than the dwelling of a commercial officer. This nation has fallen quite into obscurity in these parts, for its want of money and influence; so that the natives last year refused them lodging there; upon which their superintendent repaired to Quilon to dwell for a time under our protection" Of Kulachel the Abbe Raynal writes thus about 1760: "The factory of the Danes at Kollachy is nothing more than a small storehouse where they might nevertheless be supplied with two lakhs of weight of pepper. But such is their indolence or their poverty that they have made but one purchase and that of a very small quantity these ten years." Kunchan Nambiar, in his enumeration of foreign powers on this Coast about 1750, makes mention of only three viz., Paranki or the Portuguese, Lanta or the Dutch, and Inkriyes or the English. These three have, one after another, held in their hands the control of Malabar commerce ever since the beginning of the sixteenth century A.D.

The Portuguese were the first in the field, and the genius of Albuquerque6 easily secured an Oriental empire for them. But they were not to retain it long. Portugal itself was overrun by Spain in 1578, and though the former regained her liberty in 1640, the mismanagement of her possessions in the East had been too gross in the interval, to be wholly remedied afterwards. The Synod of Diamper in 1599 was the last great event in the history of that nation in Malabar. For some 60 years more, they continued to hold some settlements on the Coast. But their power had gone, and the natives no longer feared them. It was a period of indolence and luxury and of indigence and vanity. Other nations had now appeared on the scene, with greater vigour and stronger will. The Dutchmen were now going to have their turn.

The success of this nation in the East Indies in the seventeenth century was as rapid as it was remarkable. It was only in 1602 that the Dutch East India Company was formally organized, but in the course of the next fifty years they founded numerous settlements all along the Coast from South Africa to New Guinea and dislodged the Portuguese from most of their strongholds, destroying upwards of 300 of their vessels. The conquest of Ceylon was completed in 1658, and in 1660 a powerful fleet under the command of Admiral Van Geons started for Malabar, with the ostensible object of replacing Rajah Vira Kerala Varma of Cochin on his throne, but really to drive the Portuguese away from the Coast.

Quilon was the chief Portuguese possession in Travancore. This was attacked on the 8th December 1660 and captured without the least resistance. There had been only thirty Portuguese stationed in that city, who, having had some notice of the arrival of the Dutch, left the fortress, in charge of the native contingent, 800 strong, some fifteen days earlier and fled to Cochin. The natives had resolved to murder all the invaders except a few who were to be sent as prisoners to Portugal. As Van Geons came to know of this, no quarter was given to the enemy, and the whole town was pillaged and burnt for several days. The garrison was pursued as far as Azhikkal in the north. All the churches were pulled down with the exception of that dedicated to St. Thomas, and the old fortifications were considerably reduced. In 1662, Cranganore and Cochin were taken from the Portuguese which practically made the Dutch masters of the entire commerce of Malabar.

In the same year, a treaty was concluded with the Queen of Quilon, according to which her palace and great guns were restored and a large sum of money paid to her by the Company for the loss that they had inflicted upon her territories in the recent war. In 1663, and 1664, alliances were entered into with almost all the principal princes of Travancore, the chief of which is. dated the 21st February in the latter year. The Company was represented by Captain John Nieuhoff, and the kings of Karunagapalli, Travancore, Quilon and Kottarakara were parties to the transaction. Nobody, after this treaty, was to import, sell or exchange any amsion (opium) into these countries except the Dutch East India Company. No one was permitted to export pepper or cinnamon out of the country or to sell them to any one except to this Company. A certain price was settled, between both parties and what share each should have in the custom, whereby all former pretensions and exceptions were annulled. Treaties of a similar nature were concluded also with the kings of Kayenkulam and Pirakkad. In 1667 the four chief settlements of the Dutch on this Coast, Quilon, Kayenkulam, Cranganore and Cannanore, were placed under the command of the Dutch Commodore at Cochin. The Portuguese became altogether powerless, and the English who had owned two settlements in North Travancore viz., at Karunagapalli and Pirakkad were driven away thence as also from Cochin.

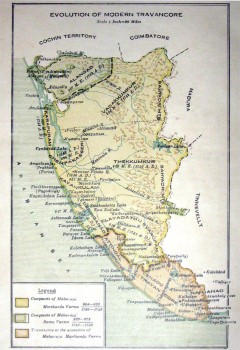

Divisions of Travancore in 1660. Travancore at this time was divided into the following kingdoms :

- To the extreme south lay the kingdom of Travancore. The great Tirumala Naik of Madura invaded it in 1635, and as his invasions were often repeated, an army of 10,000 soldiers was maintained by the king. His territories extended from Cape Comorin to Quilon with the exception of Parur which was under the direct sway of the Queen of Jayasimhanad or as the Europeans called it Signati The chief town was Padmanabhapuram, which was surrounded by a wall 24 ft. high. The royal palace was surrounded by another stone-wall. Kottar was a town of great traffic. Cape Comorin, Tiruvellam and Varkalay were places of pilgrimage. Many Mahomedans inhabited the towns of Tengapattanam, Kuzhithura and Katiyapatnam. Suchindram was a large and populous city. Verrage or Tiruvettar was a very famous town. At Attingal lived the female members of the royal family. The Travancore king alone, of all the chief rulers of Malabar, did not treat the Zamorin as his suzerain. He also seems to have taken a mediator's part in the disputes among the other Malabar kings, for we see him finding fault with the Dutch Company for driving Godavarma Rajah (Gondorma) of Vettatnad from Cochin.

- Jayasimhanad, otherwise called Quilon, was a small principality extending as far as Azhikkal in the north and Parur in the south. Its princes were closely allied to the kings of Travancore and in 1600 the eldest member of the Quilon or Travancore royal family appears to have ruled over the whole country of Venad from Quilon to Cape Comorin. At the time of the Dutch invasion, the State was subdivided into three or four minor powers which cannot be correctly identified at present.

- Peritalli. This is said by Nieuhoff to have been bordering upon the kingdom of the Naiks of Madura in 1660. It had no sea-coast, and according to Visscher, extended as far as the mountains in the east. About 1710 it was united with Kayenkulam by adoption. Francis Day says that it was seized in 1734 by the Maharajah of Travancore along with the Elayeda Swarupam with which it had been united a few years previously. Both Visscher and Day cannot be right. It is believed that the country referred to must have been Nedumangad.

- Elayeda-Swarupam was another principality that lay to the east of Jayasimhanad. It included Kottarakara and Pattanapuram, Shenkottah and Kalakkad. Heer Van Rheede in 1694 remarks that Terivancore (Travancore) could collect 100,000 soldiers, Attingen which, being under the direct sway of the Queens of Travancore, is treated separately by European writers, 30,000, Eiayedaswarupam 50,000, Peritalli 3,000 and Quilon 30,000. All these, however, were once portions of Travancore, and so Rheede calls the whole territory by the name of Tippopposorivan or Trippappur Swirupam.

- Karunagapalli or Marta, so called from its chief town Maruttakkulangara was another principality to the north of Quilon, In 1660, it was ruled by an old and intelligent monarch. The Mahomedans settled here in considerable numbers from Cannanore and monopolised the trade. It extended as far as Kayenkulam in the north and Azhikkal in the south. Mavelikkara was a portion of the kingdom with Putiyakavu as its chief town. It became subject to Kayenkulam before 1720.

- Kayenkulam claimed the second rank among the kingdoms of Travancore. Even in 1599, Travancore and Kayenkulam were at war concerning the possession of Kallada, a town in the Quilon Taluk. The Rajah of Kayenkulam became very powerful after the possession of Karunagapalli and Peritalli and would have taken Quilon also in 1731, but for the foresight of Maharajah Marthanda Varma.

- Tirukkunnappulay or Karthigapalli was another small kingdom, stretching inland to a considerable extent. Visscher says it was ruled by a powerful monarch of great authority. It seems that about 1730, this territory also formed part of Kayenkulam.

- Pantalam or Panopoli lay to the east of Kayenkulam. Visscher says it had merged in 1720 into Kayenkulam by adoption. This appears somewhat doubtful.

- Ambalapuzhia or Pirakkad was a powerful kingdom. The Rajah, when Nieuhoff visited him in 1662, knew the Portuguese language perfectly well. No theft was known in his territories. Kutamalur inland, and Pirakkad were the principal towns. "We were forced to go by water" writes Nieuhoff "through several channels and rivers, the country thereabouts being full of both, like Holland, affording scarcely any passage by land, but by the dykes, all the rest being rice-fields curiously planted with trees on all sides." The country bordered to the north on Cochin and to the south on Kayenkulam. Most of the king's revenue was obtained from pirates on the Coast.

- Tekkumkur or South Vempalanad was an independent kingdom. The Dutch do not appear to have had any factory in this kingdom. It embraced the Taluks of Tiruvella, once belonging to the Brahmans, Changanachery and Kottayam. Visscher says in 1723 "The Rajah possesses a beautiful territory superior to any other I have yet seen in Malabar. This country is also very populous and possesses roads and a fresh and pleasant climate."

- Vadakkumkur or North Vempalanad was a large province though not very powerful. The Dutch East India Company did not conclude any treaty with this king first, but afterwards built a factory at Vechur.

- Punjar ruled over the mountains of South Todupuzha and Minach.il. It is never mentioned in Dutch and Portuguese works and like Pantalam, seldom entered into any relation with other powers in the country.

- Alengat or Mangat included Alwaye and extended as far as Malayatur in the east.

- Edappali or Replien was a principality in the Kunnatnad Taluk.

- Parur under a Brahman lord also held independent sway. The Rajahs of Ambalapuzha, Vaddakkumkur, Alengad and Parur were bound to assist the Rajah of Cochin against the Zamorin in return for which they had a voice in the election of a new prince to the Cochin throne. It is indeed with pardonable impatience that Nieuhoff, after an enumeration of their kingdoms, remarks in conclusion, "On this Coast there are so many petty kingdoms that it requires no small time to distinguish and know them from one another.

Thus the Dutch soon monopolised the whole trade of Malabar. Dr. John Fryer says about them in 1675 "Carnopoly is some miles to the north of Quilon, formerly inhabited by the Portuguese from, them taken by the Dutch who have built a castle there an lord it over the natives, so that at Carnopoli, the Dutch exact custom for all the goods they carry off to sea, though there live but one boy and two Dutchmen.. .The Dutch will leave nothing unattempted to engross the spice-trade; for none has escaped but this of pepper: Cinnamon, aloes and nutmegs are wholly theirs, and by the measures they follow, this also in time must fall into their hands. Nor indeed are pretensions wanting, they holding here their right by conquest (a fairer claim than undermining). They boat in a manner they have subdued the natives which, is no hard matter, since this region in Malabar is divided into petit signiories or archebels against the Zamorin of Calicut." The Dutch had concluded alliances with all the Malabar princes and thought that these had secured them the monopoly of the entire trade of Malabar. They saw, however, only later on, the utter folly of their proceduie. As Stavorinus writes in 1776 "One of the principal objects of the Company in expelling the Portuguese from this Coast was to become possessed of the pepper trade exclusively of all the others, to which perhaps, other reasons of a political character might be added. They, however, met with much disappointment on this head, both by the bad faith of the Malabar princes and by the constantly increasing competition of European rivals who adopted a surer mode of obtaining as much pepper as they wanted by following the market price or even paying something above it, while the Dutch Company continually insisted upon the performance of contracts that no pepper should be furnished to others." As an instance of this may be mentioned the incident that when the Rajah of Karunagapalli asked Captain Nieuhoff what quantity of pepper the Company might require, he replied that they wanted the whole and would have nothing in parts. The selling of pepper to other nations was stigmatised as contraband trade which ought to be put a stop to by compulsion if other means were not sufficient, and force was resorted to at different times to effect this object. But the princes themselves, even if they had the will, had not the power to restrain their subjects from carrying on trade with foreign nations. The Dutch, therefore, from, the beginning had to dazzle the eyes of both princes and people with their soldiers and wealth. They had to be reckless in their expenditure and build fortifications at every point. But all these ostentations which cost the Company such large sums of money had not the effect of producing in the native princes that degree of awe and apprehension which is indispensably necessary for carrying on an exclusive trade. Smuggling was largely indulged in by the natives. Commandant Cunes wrote in 1756 that full ten cargoes of pepper i.e., between eight and nine millions of pounds' weight might be annually exported from Malabar, but that half of this was taken over to the Coromandel Coast. This ruinous policy of other European nations had been perceived even so early as 1615 by Sir Thomas Roe who writes: "The Portuguese, notwithstanding their many rich residences, are beggared by the keeping of soldiers and yet their garrisons are but mean. They never made advantage of the Indies since they defended them. Observe this well. It has also been the error of the Dutch who seek plantations here by the sword. They turn a wonderful stock; they prole in all places; they possess some of the best, yet their dead pays consume all the gain." That great Englishman was a real prophet, and the Dutch after displaying too much magnificence and ostentation at the beginning soon after resolved, at one stroke, to curtail all their expenditure, thereby exposing themselves to the ridicule of every prince in Malabar. As Mr. Sewaarderkroon wrote in 1698, “It is to be regretted that the Company carried so much sail here at the beginning that they are now desirous of striking them in order to avoid being overset.

The Chief of Cochin was called the 'Governor and Director. Colster was the first Governor of Cochin and Van Spall the last. After 1795, no Governors had to be appointed by the Company. A Council, consisting of a second who was the senior merchant, the fiscal, the chief military, & c., was organised to assist the Governor. The Secretary to this Council was a junior merchant, who had at the same time to hold the office of translator of the Malabar language and chief of the factory at Quilon. There were Dutch Residents in all important stations such as Cranganore, Kayenkulam, Pirakkatt and Chatwa. In 1686 it was suggested that, owing to the heavy expenses of the Company, all the fortifications in Cochin, Cranganore, Cannanore, and Quilon need not be kept up, the garrison in them should be withdrawn or reduced and the number of the Company's qualified servants greatly diminished. The Supreme Government of Batavia took these suggestions into consideration in 1697 and declared that the fortifications of Cochin should be reduced by one half, that at Cranganore, the Portuguese tower alone ought to be permitted to remain, and that all fortifications except the ancient interior works should be immediately demolished, and that at Quilon no more should be retained than the old Portuguese tower or as much of the existing works as might be thought necessary for the interest of the Company together with 15 or 20 men to which number the establishment there was to be reduced. It was also settled that at Pirakkad, Tengapatnam and Kayenkulam a book-keeper with two private soldiers should be placed to watch opportunities of trade. The navigation of the Malabars was in no way to be disturbed. Fortyfive pieces of iron and 6 pieces of brass ordinance with two motors were judged suffici¬ent artillery to meet all emergencies: 530 Europeans and 37 natives alone were to be employed in the military service.

More economical measures had to be adopted as years advanced. In 1723 Visscher wrote that though a ship of 145 ft. was sufficient to provide all the Dutch settlements on the Malabar Coast with both the merchandise and provisions requisite for a year, the maintenance of the garrison, its munition and its servants cost the Company a very large sum of money. Further, a new dispensary, rice-ware-house, hospital and powder magazine and a new fort each at Chetwa and Pirakkat were built by the Dutch on the Malabar Coast. They had also many expensive wars with native princes, the one of 1717 itself costing them, nearly two million francs. As a consequence of this, the Supreme Government of Batavia already urged their representatives in Cochin to desist from keeping up continual warfare and to endeavour to live in peace with their neighbours. The expenses of the Company nevertheless increased, and the only three reasons according to Visscher why Dutchmen still desired to retain their possessions in Malabar were to preserve the monopoly of the pepper trade, to use Cochin as a provision-station for vessels and to make the same town serve as an outpost to protect Ceylon against the attacks of other European nations. In 1739, Van Imhoff suggested two expedients for the retention of the trade monopoly of Malabar by the Dutch, viz., either to follow the market-price in the purchase of pepper or to imprison all the refractory princes and thus enforce their contracts. The first of these methods appeared to him to be both unprofitable and unjust, and so only the second was advised to be pursued. Thus the craze for monopoly only increased as pecuniary loss became more and more felt, and in 1740 a new treaty was concluded with the Raja of Edappalli according to which he was obliged to deliver up all his pepper to the Company. So miserable indeed did the situation become in the course of two more years that in 1742 when Commandant Golonesse wrote to the Supreme Government of Batavia, that Malabar was, in spite of the expense undergone in its maintenance, one of the most important possessions of the Dutch Company in the East Indies, the Governor-General Mossel made the desperate reply: "I am so far from being of your opinion that I rather wish the ocean had swallowed up the Coast of Malabar, an hundred years ago." In 1745, the expenses and losses of the establishment increased so much that notwithstanding all the profits during the five previous years, the pay ran greatly into arrear. Three wars were waged in three different continents, Africa, Asia and Oceania at one and the same time, which set the Company materially backwards in their East Indian affairs. Some fifteen years later the Abbe Raynal notes: "The events have not answered their expectations. The Company have not succeeded in their hope of excluding other European nations from this Coast. They procure no kind of merchandise here but what they are furnished with from their other settlement and being rivalled in their trade, they are obliged to give a higher price here than in the markets where they enjoy an exclusive privilege." The same author gives in p. 219 of the first volume of his 'History of Trade Settlements’ a detailed account of the losses till then sustained by the Company. The only three articles of commerce that the Dutch got in large quantities were coir, fish salted by dipping it several times in the sea and cut into pieces of the thickness of the length of a man's finger and sent in ships to Acheen, and cowries collected by women and put into parcels each containing about 12,000 of them. They sold chiefly alum, camphor, sugar, iron, lead, copper and quicksilver. In 1779, it was found that the expenses of the Company amounted to 489,645 francs, while the income came only up to 414,977. Stavorinus well sums up the case when he writes "Malabar is not one of the most advantageous or important possessions of the Dutch in the East Indies. It costs the Company much money on account of the destructive wars in which they have in consequence engaged, the rivalry in trade of numerous competitors and though last, not least, the infidelity and peculation of their servants.

But the most important cause of the decline of the Dutch supremacy on the Malabar Coast was the ruinous war that the Company carried on against Maharajah Marthanda Varma of Travancore in the eighteenth century. It has been observed before that the Travancore king was a party to the treaty of 1664 with the Dutch East India Company. But soon after, the relations between the two powers became considerably strained. The English had first occupied Vizhinjam and Kovalam, but after the factory of Anjengo was built in 1695, that became the centre of English trade in Venad. The Dutch had only one important factory in the country namely that at Tengapatnam, but as Tuticorin on the other coast also belonged to them, the former served as a convenient port for collecting Malabar goods and dispatching them thither. For some time it seemed that the Dutch alone would be shown consideration in the Maharajah's court. The early English settlers in Travancore did not pay scrupulous respect to the customs and prejudices of the natives. If we may believe Visscher, some English merchants seized a Brahman Pandit and compelled him to shave the beards of their slaves, in return for which the native blockaded the port of Anjengo and inflicted heavy disaster upon the Company. This unfriendly relation was, however only momentary and destined to pass away soon.

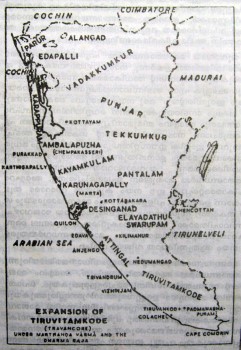

With the beginning of the reign of Maharajah Vira Marthanda Varma, a change manifested itself in the foreign policy of Venad. Marthanda Varma was a born conqueror. Assisted in a spirit of the purest self-sacrifice by Rama Ayyan Dalawa with whom Eustace D’lanoy subsequently joined, and after the death of that great minister, by Ayyappan Marthanda Pillai Dalawa, the Maharajah was destined to play a memorable part in the history of Travancore, a part which had for its result the unification of several warring principalities under a mighty ruler. It was the genius of Marthanda Varma that evolved order out of the chaos that had brooded over the country, and it was also due to his great vigour and energy that the petty principalities of Travancore were welded together into one homogeneous and compact whole. Abbe Raynal writes of this sovereign “The father of Karthiga Tirunal Maharaja added more dignity to his crown than any of his predecessors. He was a man of great abilities... The interior parts of his country were benefited by his conquests, a circumstance that rarely happens." Father Paulinus writes" Vira Martanda Pala was a man of great pride, courage and talents; capable of undertaking grand enterprises and from his youth had been accustomed to warlike operations," The native poet Ramapurattu Variyar says the bare truth when he sings മാര്ത്താണ്ഡാഖ്യയായിരിക്കും പ്രത്യക്ഷദേവതയുടെ മാഹാത്മ്യമോര്ത്തിട്ടു മനസ്സലിഞ്ഞിടുന്നു He was not merely an admirable conqueror and kirig, but also one of the noblest and most pious-hearted men whom India has known.

The foreign Dutchmen became the mediators of disputes in Malabar royal houses in the early decades of the eighteenth century and in 1734 four different deputations waited on Commodore Maten, the Governor of Cochin, from four princes of Malabar. One of these was that of the Rajah of Kayenkulam, against the Rajah of Travan¬core who had been preparing to attack his territories. The Governor first refused him aid ; but subsequently informed the Maharajah that expedition ought to be made against Kayenkulam and that as the annexation of Kottarakara was an illegal act that territory ought to be restored to the surviving Rani. To this the Maharajah did not hesitate to reply that it was an unfortunate circumstance that foreigners should be called upon to arbitrate among native princes, and that the Dutch East India Company had nothing to complain of so long as their commercial relations with Travancore did not undergo any change. On the 6th July 1739, Van Imhoff, Governor of Cochin, wrote to Batavia that the king of Travancore having been always successful in the wars which he had undertaken, had made himself so far respected by all the chief princes of the Malabar Coast, that he was looked upon by every one with eyes of jealousy and apprehension. He further observed, that besides making it impossible for the Dutch to maintain a balance of power among the rulers of Malabar, that prince had wholly attached himself to their competitors, namely the English, whose increase of power could not but be pregnant with the most alarming consequences to the interests of the Company. The Rajah, he added, merited some severe chastisement for his insolence, at the hands of the Company. Without even waiting for a reply the same Governor proceeded to Trivandrum at the beginning of the next year, and after a good deal of discussion with the Maharajah said that the Dutch had resolved upon an invasion of the Travancore territory. The Maharajah suddenly broke up the conference with the sneering remark that he too had been thinking of some day invading Europe with his manchis and fishermen.

Thus the Travancore-Dutch war began in 1741, and lasted for seven years. It was the greatest and the most frightful war into which Travancore was ever called upon to enter, and the names of Marthanda Varma and Rama Aiyyan will always be remembered with patriotic pride by every native of this country, in connection therewith. The Dutch reinstated the Rani on the Elayedaswarupam throne. But the Travancore troops defeated the Dutch in the battle of Kottarakara and drove the Rani to Cochin. We read in the Dutch records of Cochin that the Rani was given an allowance of two rupees five annas; probably per day. Every Dutch outpost as far as Quilon was immediately evacuated, and the widest consternation prevailed in the Company's camp.

In the meanwhile, Imhoff's Ceylon army had landed at Kulachel in South Travancore and advanced as far as Eraniel. The great warrior Rama Iyen took the field against them on the 10th April 1741 and at Kulachel gained a complete victory. It was here that Eustace D’lanoy, afterwards Captain of the Maharajah's bodyguard battalion was taken prisoner. The Dutch then rendered every assistance to the Kayenkulam Rajah and other chiefs with whom Travancore was at war, and in 1743 captured the fort of Kilimanur to make a sudden dash at Attingal where the Travancore princesses lived. The Maharajah immediately started with his nephew, after¬wards the famous Rama Varma Kulasekhara Perumal, his trusted minister Rama Iyen and Captain D’lanoy and arriving at Kilimanur besieged the fort. The Dutch garrison held out for six days, but being defeated in the end, beat a precipitate retreat to Quilon, along with the Kayenkulam Rajah and Commandant Golonese.

Peace conferences were held at Mavelikara and Parur without effect. The Dutch simply wanted to gain time for obtaining instructions from Batavia. At last on the 18th of October 1748 the draft treaty was sanctioned and on the 15th of August 1752, finally ratified by the Batavian Government. A summary of the conditions may be found in Mr. Sankunni Menon’s History, all of which were more or less favourable to Travancore. Two articles, the 9th and the 20th, deserve prominent notice. The first stipulated that the Company should recede from all engagements which they might have entered into with other Malabar princes whom the king of Travancore might choose to attack and on no account interfere in their disputes and afford them assistance or shelter: nor in any respect raise any opposition to the enterprise of the king.” This was “observes Stavorinus” the chief object of the king of Travancore and that in which he most interested himself. Filled with the intention and fired with the idea of making extensive conquests, he knew no obstacle so powerful to prevent the accomplishment of his desires at the power of the Company.” The 20th article demanded that the Dutch should annually supply Travancore with the following articles, at the stated prices mentioned below:-

£ s. d. each

One fire-lock 1 1 0

100 gun lints … … 0 1 2

100 leaden musket bullets 0 1 3

and some iron work and brass cannon to the value of Rs.2000, in return for which the Maharajah was to sell them 3000 candies of pepper from the territories he already owned and 2000 candies more from those which he might subsequently acquire at 57 and 55 Rs. per candy respectively. 4 fanams per candy was fixed as the export duty. According to the 24th article, an annual present of £44 was agreed to be given to the Maharajah. The cutcha cloths of Kottar and Kulachel were largely in demand even at the end of the 17th century. They had been first sold to the Dutch at Tuticorin, via, Tengapatnam, but afterwards to the English at Anjengo. By this treaty the Dutch secured all the surplus cotton cloths of Travancore for themselves on the payment of a considerable sum of money. “The treaty” writes Dr. Day “does not appear to have brought either credit or money to the Dutch.” Thus ended the great war with Travancore from whose enervating effects the Company never recovered. The Dutch had to throw over all their native allies, as they had pledged to leave them absolutely to the mercy of Travancore. The princes saw the utter helplessness of their situation and made at once a united appeal to the Zamorin of Calicut to invade the Dutch factories in Malabar and Cochin. Commandant Cunes immediately applied to the Maharajah for assistance, but he merely replied that he had told the ambassadors of the Zamorin to dissuade their master from doing so. On the 18th of October 1756, the Zamorin sent Ezekiel Rabbe a Jew to Cunes, proposing favourable terms if they would join him in attacking Travancore; but the Governor merely wrote to Batavia "Should Travancore refuse to join us, it becomes the more urgent, that your excellences should furnish sufficient forces, to enable us to assume a commanding position merely to overawe these Malabar chiefs and thus to continue on terms of the most intimate friendship with Travancore, without the slightest room for any misunderstanding.” And so the Zamorin's proposal came to nothing, Commandant De Jong succeeded Cunes as Governor. Fearing that the Maharajah whose dominions had now advanced so far as Cochin would take possession of Chetwa as well, the new Governor proposed to fix certain limits for the Dutch and Travancore territories. This irritated the Maharajah who said that the Company must be content with the delivery of pepper and other products in such a manner and in such quantities as he chose to allow and that he did not pretend to look upon them in any other light than that of merchants who were not possessed of any territorial jurisdiction or supreme authority, and who ought to follow the market prices in paying for such purchases. The cotton cloths of South Travancore were thereafter sold again to the English at Anjengo. The Dutch Company resolved to put up with all these indignities without a word of murmur. They had thoroughly known the strength of Maharajah Marthanda Varma’s arms, and they durst not, for all the world, quarrel with him again.

The time now arrived for the final departure of the great Maharajah. It was the month of July in 1758. Plassey had been but recently won by Clive, and in all Southern India the English were still looked upon as a weak nation. Marthanda Varma called to his bedside the heir-apparent to the throne and said to him in all solemn sincerity: "These Englishmen appear to be destined to rise to such power and glory as are hitherto unparalleled. Be it your constant aim and endeavour to secure their friendship and support." The subsequent history of Travancore has well shown how far these prophetic words were respected, not only by his immediate successor, but by every ruler who has thereafter sat on this ancient throne.

One of the earliest acts of Maharajah Rama Varma was to throw open two new ports for public trade, one at Puntura and the other at Alleppey. The Dutch factory at Pirakkad became useless in consequence, and Father Paulinus writes that the Dutch revenue went down considerably thereafter. In 1767 the Company's losses became thoroughly unbearable. Strict orders were received from Batavia to destroy the forts of Chetwa, Quilon, and Cranganore' which, however, the Cochin Governor did not think it in the Company's interests to carry out then. In 1771 Adrian Moens became the Governor. Hyder applied to him for a free passage for his troops through the Dutch settlements to Travancore. The Governor tried to effect a triple alliance among the Dutch, Cochin and Travancore, but the Maharajah said that as he had already entered into a treaty with the Nawab of Arcot, he could not take the offensive without losing the support of the Nawab. He, in fact, relied more upon the strength of his frontier lines in the north and the support of the English than a renewed alliance with a fallen power. After the success of Hyder Ali's ambuscade at Chetwa, the Company became thoroughly disheartened. All the Malabar settlements of the Dutch had now become subject to Mysore. Orders were again dispatched from Batavia to sell all the Company's forts, and Quilon was sold to Travancore in 1770 for a lakh of rupees. The price of pepper per candy had been in the meantime raised to Rs. 115 from 57; but in 1790 the Maharajah refused to furnish any, unless a higher price was agreed to be paid by the Company. Before 1793 Van Angelbeck, the Governor, sold all the factories and lands that the Dutch possessed in Travancore and Cochin to the princes of those two States respectively. Cranganore and Ayikotta fell to the share of Travancore, and only Cochin, the Capital of Dutch Malabar, remained to be disposed of. In the beginning of 1795, Van Spall became Governor of Cochin. Angelbeck at the time of his leaving office directed his successor not to permit the English to interfere in the affairs of Cochin 'for' wrote he "if they are allowed to insert their little finger in the affairs of these regions they will not rest until they have managed to thrust in the whole arm." But Providence did not leave it to the choice of the Dutch Governor to permit the English to become pre-eminent in the councils of the Rajahs on the West Coast. The army of the Revolution had marched from France, and driving the Stadtholder thence to Great Britain, occupied the Netherlands, without hindrance or opposition. The unfortunate refugee issued a general command to all the Dutch Governors and commandants of stations that English troops ought to be permitted to occupy them all, lest the French should take possession of them. On the 3rd of March 1795, directions were transmitted from the India Office, to seize all the Dutch East India Company's possessions in the East. On July 23rd, Major Petrie marched from Calicut to Cochin, and forced the Governor to capitulate on condition on the 19th of October. All the settlements of the Company in the East Indies were occupied by English troops. In the redistribution of dominions among the various European powers after the banishment of Napolean, Holland got Java back, but not Cochin, the only Malabar settlement she owned in 1795.

Thus concludes the history of the Dutch on. the Malabar Coast—a magnificent beginning, a melancholy end. A Portuguese priest at Goa was once asked by a Dutchman, "When do you imagine the sway of my countrymen will die away like that of yours in India" "As soon" he replied "as the wickedness of your nation shall exceed that of mine" The Dutch can nevertheless, be scarcely said to have been positively wicked. Sir William Hunter says "The fall of the Dutch colonial empire resulted from its shortsighted commercial policy-It remained from first to last destitute of sound economical principles." The Dutch have not left many marks of their ascendancy on this Coast, presenting themselves in this respect a sad contrast to the Portuguese. They have no doubt influenced the architecture and vocabulary of this land, but only to an inappreciably small extent. "The failure of the Dutch policy," notes Dr. Day, "should be a warning to other nations" Their appearance in Malabar was like that of a meteor in the sky. They shone forth in their full lustre for a moment and then disappeared for ever.

Notes and References

This paper reprinted from an old number of the Malabar Quarterly Review, traces the growth and decline of the Dutch Power in Travancore. 'Their appearance in Malabar', says Ulloor ‘was like that of a meteor in the sky; they shone forth in their full lustre for a moment and then disappeared for ever.' The Dutch failure was due to political developments entirely beyond their control Like other foreign powers the Dutch also pursued a policy of peace and war with the kings in Travancore, always keeping an eye on the expansion of their trade. They created conditions favourable for the revival of trade in Kerala. As a result ports like Cochin Quilon, Anjengo, Colachel and Tenga Patanam hummed with brisk activities. In the educational and cultural fields their impact has been very little. Their greatest contribution here is the monumental botanical work Hortus Malabaricus which gives in detail the medicinal properties of Indian plants. The Dutch were the first protestant nation of Europe to establish trade contacts with Kerala by challenging the Portuguese monopoly.

1. The Chief French Settlements on the coast were first Tellicherry and Calicut and afterwards Mahe.

2 Their cheif station in south India was Tranquebar on the Coramandel Coast.

3. Pinkertous Collection of Voyage and Travels Vol. III., p. 383.

4. French historian and thinker Raynal's History of the settlements of Trade Vol I., p. 367.

5. Kunchan Nambair's Nalacharitham Thullal, Introduction.

6. Alfonso de Albuquerque, the Portuguese admiral who founded their empire in the east.

7. Francis Day's The land of the Perumals’ (pp. 11 & 114) give good information about Cochin and Travancore in the 19th Century.

8. The History of Christianity' by Hough is an English translation of the proceedings of the synod of Diamper. A Latin copy of it is still kept in the Roman archives of the Jesuits.

9. Hunter's Imperial Gazetteer, Vol VI, p. 361.

10. J.C. Visschcr, Dutch Chaplain at Cochin, His Letters from Malabar contains copious. Information about the political and social life of Kevala during the Dutch period, These letters formed the basis of the monumental History of Kerala by K,P, Padmanabha Menon,

11. Visscher's Letters, from Malabar, P, 59.

12. Day's Land of the Perumals, P, 130

13. Pinkerton's Voyages Vol. VII

14. Hugh's Christianity in India. Vol II. p. 17.

15. Fryers Voyage to the East Indies p. 55. Dr. John Fryer visited Cochin and Calicut in the course of his voyage in India (1672-1681) and left a record of it.

16. Stavorinus's Voyage Vol. Ill, p. 271.

17. Neiuhoff and Baldacus both Dutchmen have left letters and accounts which have been of inestimable value to scholars of the later period to reconstruct the history of Kerala.

18. Stavorinus's Voyages Vol III, p. 220.

19. This date has been given by Stavorinus. Dr. Day takes the event to. 1680, on what authority it is not known.

20. Van Imholf guided the affairs of the Dutch when Marthanda Varma came to power.

21. William Hunter: A British civil servant, who organised and directed statistical Survey of Indian Empire—It was published as 'The Imperial Gazetteer of India.'

22. English essays and poems by Mahakavi Ulloor Kerala University Publication 1978)